Belen Gallardo was 11 years old when she left Ecuador for Madrid in the face of historic economic collapse that was not only disastrous for her family but also for her country. She and her siblings thought they were going on a holiday. Little did they know it would be years before they returned to live in Quito, without their parents.

RELATED:

Suicides and Despair: The Legacy of Ecuador’s Banking Crisis

She was one of some 2 million Ecuadoreans who left the country in the wake of a banking crisis that spurred massive personal losses and divided families across the globe as the government put the interests of private banks over that of hard-working citizens. In recent years, many of these migrants have returned, and have been readjusting to a very changed Ecuador, while the effects of the crisis still haunt them.

“My dad had a small company, but when (the collapse) happened, we decided to go to Spain because the crisis was fatal,” said Gallardo. “They didn't get back the money that they had in the bank, there wasn't anything that we could do to fix it and my dad’s company just went broke.”

The Crisis Hits Hard

In the late 1990s, with lowered oil prices, a weak currency and little state control over private banks, interest rates and capital flight, Ecuador began to spiral into economic crisis. But the worst was yet to come.

On March 8, 1999, right-wing President Jamil Mahuad announced measures known in Ecuador simply as the “Bank Holiday.” For five days, bank accounts were frozen, preventing Ecuadoreans from accessing their savings.

In a series of disastrous moves, the government then froze deposits of accounts with more than US$500 for a year and instead gave out heavily devalued deposit certificates. Banks then offered to buy back the deposits at a fraction of the cost.

The magnitude of the crisis was heightened by previous laws that allowed banks to engage in spurious lending to their own directors while also making the state responsible for private bank debt.

Many were forced to choose between losing significant amounts of deposits or waiting to get back deposits that they were unsure would materialize from paper into actual money. Amid the crisis, inflation and unemployment also began to skyrocket.

RELATED:

For Ecuador's Poor, Privatized Health Care Is a 'Death Sentence'

On the back of the Bank Holiday, the foreign exchange rate of Ecuador's national currency, the sucre, took a drastic dive from 7,000 sucres to the U.S. dollar in early 1999 to 30,000 one year later. In early 2000, Mahuad then changed Ecuador’s currency to the U.S. dollar. Citizens were forced to exchange their sucres for dollars, which were now worth a fraction of their previous value. For those who had earned a living in sucres but had dollar loans, debt hit unheard of levels and many people’s savings all but evaporated.

Gallardo explained that leaving Ecuador for Spain — the largest destination country for Ecuadoreans who left in the wake of the crisis — was difficult at such a young age for her and her siblings.

“I was 11 years old and of course I had my life, my school my friends, then suddenly new people, everything was new,” she said, adding that despite being told the move was for her own good, it was difficult to adjust to the cultural change.

While Gallardo described Spain as a beautiful country and part of the “first world” with the same language and different opportunities than home, it was by no means always easy. She explained that expenses including rent, cost of living and finding work as a young person was also difficult, particularly off the back of the global financial crisis.

She returned to Ecuador in 2012, but her parents and one of her sisters still live in Madrid and because of the distance and cost, they rarely see each other expect for holidays, a fact which has been made increasingly difficult by her father’s ailing health.

Belen said that she personally did not seek help from the state when she returned, but had noticed how a number of government initiatives had seen Ecuador undergo a number of “drastic changes” for the better, which benefited working people such as herself.

“I have my son in free public childcare which is a great help, because my salary is low, I can't easily pay the bills and other costs. I pay rent, electricity, water and the basic things myself, so I think that the help from the childcare is very good for me. I don't pay anything — not one cent — and my child is really good there.”

Guillermo Lasso’s Legacy

Conservative presidential candidate and former banker Guillermo Lasso, despite denying his ties to the crisis, is widely seen as playing a part in creating and even profiting off the crisis through speculation. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands fled the country, with others losing practically all they had.

At the time of the crisis, Lasso was vice president of the Association of Banks and then later became super minister of finance under Mahuad. Lasso also co-signed a law in 1998 that made the Ecuadorean state responsible for private bank debt.

“Personally, I am not going to vote for Lasso,” she said, adding that she has been pleased with the government of President Rafael Correa and has decided to vote for the governing party’s candidate, Lenin Moreno, after witnessing “drastic” changes in the country.

“With the pain that Lasso caused me and my family I don't think I can (vote for him),” she continued. “I think that he will come and harm us again and take things from us like he did the first time.”

Supporting Ecuador’s 'Fifth Region'

Under President Rafael Correa, Ecuador began to reach out to Ecuador’s migrant community living in what was dubbed the country’s “fifth region” along with Galapagos Islands, the coast, mountains and jungle.

As part of the “return plan,” the government helped to encourage migration and transition back to Ecuador. Those who returned to Ecuador were able to repatriate their belongings tax free, were able to apply for employment assistance and were supported in starting up new businesses.

RELATED:

Analyst: If Elected, Guillermo Lasso Will Destabilize Ecuador

Indeed, for many migrants the relocation plan came at a critical time, particularly when other parts of the world — especially Spain and the U.S. — were suffering the fallout of the global financial crisis in 2008.

Meanwhile, Spain — the country with the highest number of Ecuadorean immigrants — also enacted a number of policies to encourage migrants from all parts of the world to return home, including paying for airfares.

In 2008, the Correa government declared US$3.8 billion in foreign debt “illegitimate” and defaulted on the debt. Because of the changes under the government, many Ecuadoreans were able to return home, reunite with families and start over again in their own country.

Polo Palacios is originally from the small town of Alausi in the hills of the Chimborazo province, and like many, his family’s story has been torn between Ecuador and the U.S. Even before the bank crisis, Palacios had moved to work in the U.S first because of poor economic opportunities in the late 1980s and later in 1996, when his wife was offered to transfer to work in Atlanta, Georgia.

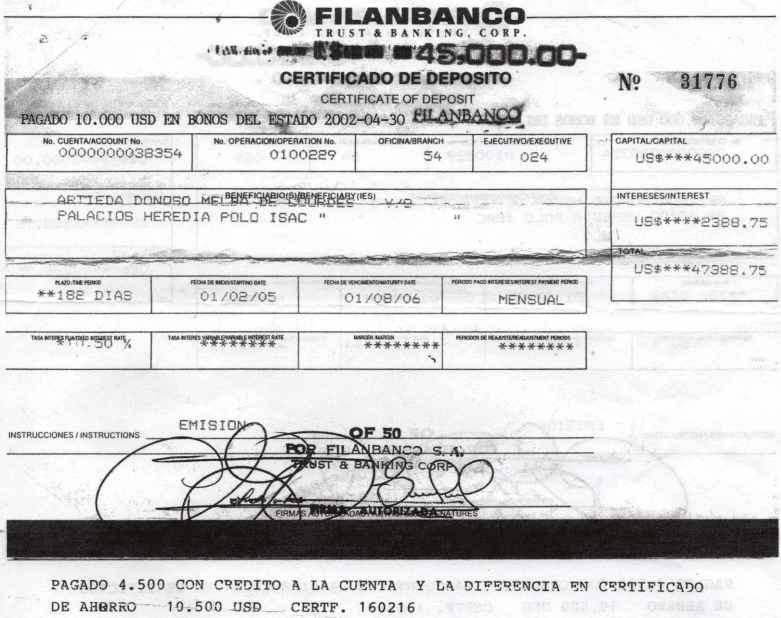

After both working for years in the U.S., Palacios’ family then became victims of what he described as “the biggest bank robbery in Ecuador.” He and his wife decided to return to Ecuador in 2001, with their two young children to invest their hard earned savings with one of the country’s largest banks, Filanbanco.

But by the end of the year, Filanbanco along with a handful of other private financial institutions had gone broke. This left his family reeling and unable to regain a US$45,000 deposit on a house in Quito. “We only had the numbers on paper and we did not know if one day we could recover that money. In us was the idea of never returning to Ecuador for the rest of our lives.”

Deciding to Return Home

Faced with little other option but to hastily sell off what they owned at a fraction of its original value, Palacios then went back to the U.S. in 2002 “with the urgency of returning to the U.S. and starting from scratch.”

When Palacios’ family returned to Ecuador in 2013, he explained that they were able to take advantage of tax exemptions for households goods and were able to “see directly the immense transformations” that the country has undergone in their absence abroad.

“Every change we saw excited us. To return to a country that provides the appropriate conditions to get ahead, because in the United States we were also affected by the so-called real estate bubble.” Palacios noted that since coming back to Ecuador permanently, many more opportunities exist for work and education, while workers enjoy more rights.

RELATED:

'Impossible': Ecuador's Electoral Missions Address Fraud Claims

Palacios said the the current opposition in Ecuador has tried to create a discourse that “pretends that they be the saviors of the country, when they were the cause of the economic bankruptcy of thousands of Ecuadoreans who forced us to leave our country.”

Aida Soto, originally from Tulcan in northern Ecuador, also left in with her family to head to Long Island, New York in the height of the crisis in May 1999. “As a family we had known that we had to make the best out of the difficult situations,” Soto said, adding that they had worked very hard in the U.S. and for the most part her children were able to adjust well to the culture and spoke perfect English.

Her family would not return for almost a decade, coming back with assistance from the government's return plan in 2008, which allowed them to bring all of their household goods back to Quito.

She described how many things had changed for the better when they returned to Quito, particularly in terms of security and lower levels of violence, but also because the country was much more stable economically that it was when they had fled.

But returning to her home country came with mixed emotions. She described being back at home with family and friends that she had not seen in over a decade as “the the most gratifying feeling.” Yet while her family had planned a year in advance to adjust to the return, “we felt like foreigners in our own country … practically everything had changed.”

Speaking of her children, Soto explained that she and her children didn't necessarily want to return, but still had a strong attachment to Ecuador and were proud of their heritage. As study and job prospects seemed difficult for her children, particularly with the financial crisis hitting the U.S. and the “prohibiting prices” of university. Always with their children in mind they decided to come back to Ecuador for their education.

“The decision to return really was because during those 10 years that we were staying in the U.S. we didn't achieve legal citizenship there,” she said. “We were there the whole time as illegals and this implicated my children in gaining scholarships to study in the universities there.”

As Ecuador’s election approaches many returned migrants are not only casting their gaze back to how the banking crisis started, but how future disasters can be avoided.

As a decade of stability and social improvements — including for returned migrants — under the Correa government comes to a close, Ecuador again sits at a crucial crossroads set to determine its economic future.