When talking about environment and development, we invariably come across the problem of defining the second. We, as human beings, somehow have a well defined concept about what a natural environment means: all natural living and non-living things, including us, the seas, mountains, magnetism and animals. But in the Anthropocene era even that definition is blurred, as human activity each time affects more and more the planet we live in, leading to artificially built environments and phenomena.

When speaking about environment and development, we invariably come across the problem of defining the second. As human beings, somehow have a well-defined concept of what a natural environment is: all natural living and non-living things, including us, the seas, mountains, magnetism, and animals but it has become increasingly difficult to define what development is. Even in the Anthropocene era that definition was blurred and since then human activity has had each time affects the plant we inhabit more and more the planet we live in, leading to artificially built environments and phenomena.

RELATED:

Peasants and Afro-Descendants Preserve Mother Earth in Colombia

Things get tricky when it comes to defining development. Mass media, universities, and other institutions emerging from euro-centric idiosyncrasies promote a linear perspective on development, aiming for a single narrative on what “improving” actually means. We're familiar with that one, exemplified by most development projects all around the world, using natural resources to impulse a capital-oriented agenda, measured by economic growth and internationally recognized coefficients.

But truth is that there is no single definition of development, as the capitalist narrative is not universal and communities, individuals and nations around the world have very different opinions and desires on how to actually improve their lives and take care of the environment.

"Throughout our history we have managed to establish an organization that has effectively meet the requirements of the projects." -Montegrande, a Chilean open-cut mining company based in Calama. Photo | Wikimedia Commons

So when it comes to defining what development means in a Nation-State, it is usually the “core,” -that is, urban centers, economic and political elites, and foreign investors (to name a few)- who end up imposing their own perspective over those who don't have the means to defend their concept of development.

Of course, development models have changed through the years and we can no longer say there is a single one of them, as new theories have emerged to propose multidimensional approaches that take into account sustainability, human capital and the environmental impact, among other ways of measurement.

But even though there are good intentions and ideal plans, taking a look into the environmental struggles in Latin America makes it seem as if we’re somehow stuck in time.

In Latin America and the Caribbean -and in most of the world-, the lowest part of the asymmetric political and economical relationship are those usually living in rural areas with great natural resources but less economic power, whether they are indigenous or not, vulnerable to the will of the economic, political and geographical core.

In order to recognize the right of indigenous people to decide over their own fate, the International Labour Organization (ILO) developed the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, also known as C169, a binding international convention ratified by most mainland Latin American countries, except for Uruguay, Surinam, French Guiana, Guyana, Panama, Belize and El Salvador. Of the Caribbean islands, only Dominica has ratified it.

But the existence of the C169 doesn't mean the states necessarily take into account different development perspectives when granting licenses or promoting projects. Numerous problems arise when implementing the popular consultations on indigenous communities regarding the use of their natural resources for “the greater good,” which could mean powering near-by industries, cities and other expressions of “the core,” leaving residual benefits in the community and serious environmental problems. It also doesn’t provide any defense for those non-indigenous communities in similar struggles and, depending on the State and their own organization, they might have no consultation mechanism.

Farmers' protest against the Tintaya copper mine, run by the Swiss Xstrata, in the Espinar community in Peru. May 28, 2012. Photo | EFE

In his article “Sustainable Livelihoods, Environment And Development: Putting Poor Rural People First,” Robert Chambers discusses different perspectives at the time of proposing, understanding and implementing development projects from “the core” to the periphery, usually represented by poor people living in rural areas.

RELATED:

Gulf Stream Change Spells More Erratic Weather for Caribbean

Even though the article was written in the 1980s, its main thesis remains highly valuable: you should put poor rural people first.

The problem with most development projects in Latin America -and the rest of the world- is that these originate in the “core,” the economic and political centers, using their own development narrative and standards. That is, they obey a center-to-periphery outward logic that ultimately leads to extractivist policies mascaraed with “social management” projects for the communities where they are operate.

The Chixoy Dam in Guatemala, Development by Force

The Chixoy hydroelectric dam, in the Rio Negro community of Guatemala, is an emblematic case of development and abuse of power in the Central American country. The ambitious project was financed by the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, and would put a wall on the Rio Negro, flooding a large area belonging to a Mayan Achi community.

They were promised relocation, money, and multiple benefits in exchange for their lands, in which their families had lived for years. Of course, there was resistance, and when members of their community went missing, they decided to complete oppose the dam.

Los gritos de terror y suplicas de 243 pobladores, en su mayoria mujeres y niños masacrados, presuntamente por efectivos del Ejercito y Patrullas de autodefensa Civil, PAC, en 1982, fueron recordados el lunes 9 de noviembre de 1998, durante la primera audiencia en Salama, Baja Verapaz a 200 kms. de la Ciudad de Guatemala, del juicio contra tres procesados por las masacres de Rio Negro en el departamento de Baja Verapaz yAgua Fria en el Departamento de Quiche.

The government of Guatemala had already been known for its high levels of repression and systematic massacres, especially since the government of Jacobo Arbenz, under the excuse of fighting insurgent leftist groups. When the Rio Negro community realized they were in serious danger and they had hints the military was approaching all adult males went hiding into the mountains, thinking the soldiers wouldn’t hurt children and women, but they were wrong.

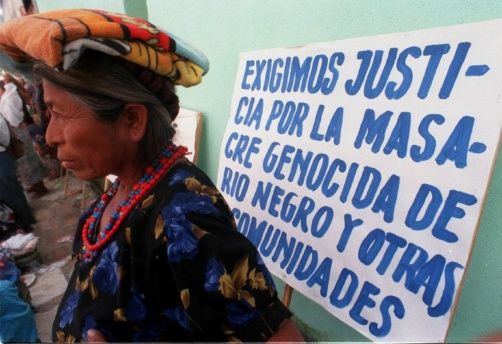

Reports say that about 400 Mayan Achi children and women from the Rio Negro community were murdered by soldiers and paramilitary group on March 13, 1982. Survivors were relocated to unsufficient and unfertile lands to which they had no kind of previous connection. The government said the operation had been part of their counter-insurgency strategy.

Survivors of the massacre have demanded justice for their murdered relatives. First hearing in Salama, Baja Verapaz, against three officers responsible for the Rio Negro massacre. November 9, 1998. Photo | EFE

Even though there have been efforts from the government to “repair the damages,” these have proved to be mere rhetoric. Days after the massacre, the future dictator Efrain Rios Montt led a military coup and made himself president. He promised reconciliation for Guatemala, but he proved to be more of the same.

RELATED:

Guatemala's Territorial Dispute with Belize About Extractivism in Mayan Lands: Activists

The hydroelectric was too big of a project to be abandoned. It represented the greater good, it would bring electric power to people and machines in far away lands. It would be a matter of pride, but now is a reminder of one of the most violent periods in the history of Guatemala. Why? Because they didn’t put the local population first.

Now, after the C169 was signed and the “democracy” was restored in Guatemala, the State is still criminalizing social movements trying to defend their territories and natural resources against mega-projects that would flood their lands, cut up their mountains and pollute their rivers.

In 2005, the Guatemalan Energy and Mines Ministry (MEM) granted three mining licenses over a third of the San Juan territory to Cementos Progreso without prior consultation with the indigenous people, thereby violating C169 and multiple articles of the national law codes.

The local population opposed and in 2007 twelve Mayan communities affected by Cementos Progreso's project carried out a community query to decide on the matter. About 9,000 people (99 percent of the consulted population) vote against the development of the projects, arguing the cement company's activities would severely damage the environment and represented a serious violation to the local population's will and territorial integrity.

Although the affected communities decisively opposed the construction of the plant, the Guatemalan government decided to go ahead with the licenses, tackling the opposition by accusing its leaders of murder, kidnapping or terrorism. The plant was built in 2013, and some of the community leaders were arrested, including Abelardo Curup, who recently died in custody accused of triple murder and sentenced to 150 years in prison. The same strategy is still used under Jimmy Morales’ administration.

A sign at the El Tambor gold mining project reads "Life is worth more than gold. No to mining." The San Jose del Golfo community in Guatemala opposed to the mine, in an area known as "La Puya," and they have been the target of violent and legal attacks from both the company and the government. Photo | EFE

Vista de la entrada de la mina de oro "El Tambor" en la que se observa un cartel de protesta contra la explotación minera, en la población de San José del Golfo, a 25 kilómetros de Ciudad de Guatemala hoy, jueves 14 de junio de 2012. Una líder comunitaria guatemalteca, opuesta a la explotación minera en esta población, fue herida de gravedad en un atentado a tiros en su contra el pasado miércoles en inmediaciones del lugar.

These kind of projects obey an outward, up-down logic, that ignore the will of the local population trying to protect their territories, their means of life, adopting a perspective that puts the long-term benefits of having a healthy environment instead of palliative-oriented, short-term development projects for the people. They don’t take poor people living in rural areas as the starting point.

Barbuda, Communal Paradise on the Risk

When Britain finally abolished slavery in all of its colonies, the recently freed women and men of Barbuda, one of the Caribbean islands that now make up Antigua and Barbuda, developed a communal land property system, which allowed everyone of them to use a piece of land by requesting a local, autonomous council.

Now, after more than 150 years and the Category 5 Irma Hurricane that devastated most of the island infrastructure, the president of the two island nation Gaston Browne is pushing to end the traditional customs of Barbuda and privatize land ownership in order to attract tourism-oriented foreign investment.

In a move that could be inspired in a Shock Doctrine manual, Browne is intending to derogate the Barbuda Land Act 2007, which protects the communal ownership system of Barbuda, to pass a “Paradise Found Act” that allows for foreign investment with the excuse of helping the island to recover from Irma, opening the way for development at the expense of Barbudan's rights over their own land.

“Selling the island as a commodity will just be the end of our utopia – what we know as paradise,” Annette Henry, manager of a Barbudan social media group, told Reuters.

As most of the Caribbean, the Antigua and Barbuda government didn’t ratify the ILO conventions. And being an afro-caribbean community, Barbudans don’t have access to those mechanisms that indigenous people do.

RELATED:

Mexico's Green Party Law to Allow Open Cut Mining and Fracking

Their council is opposing the move and activists are doing their thing, but the greater good of development and reconstruction is -not to mention huge profits- are pushing Browne into land privatization.

A Spanish cruiser arriving to Saint John's port in Antigua and Barbuda. Photo | EFE

The Alternatives

“We're supportive another more sustainable life project for our communities, based in recovering our traditions, our original seeds and medicine,” said members of the Resistance Group Against the extractivist model in Chiapas, southern Mexico.

The group integrates several indigenous and “mestizo” communities and organizations in the fight against hydroelectric plants, mines fighting, wind farms and several other mega-projects threatening environment and means of life.

They warned about increasing (para)militarization and the establishment of Special Economic Zones (ZEE), which will only cause more poverty, pollution and less workable lands, representing an “attack against sovereignty” of the people.

One can find groups like this all across America, trying to make themselves heard among the interests of private companies and the State. Cities and societies need resources, and they need to take it somewhere, but the people sitting on them want to preserve them.

The National Indigenous Congress (CNI) in Mexico developed a grassroots platform for discussion among indigenous groups in defense of people and the environment, which they consider fundamental for their own survival. In their struggle, they have formed a network of people in struggle across the country, including mestizo and Afro-Mexican communities.

In order to have real multidimensional development, this is the people we need to be hearing. All across America you can find examples, from the Mapuche struggle in Chile and Argentina to the fight for water in the Californian peninsula, going through the Amazons threatened by logging, mining and ranching.

Projects coming from an up-down, outward logic will always meet resistance and translate in repression and polarization. Changing that logic could relieve tensions and protect the environment. And in the end, nobody knows what’s really best for the other, and if the communities actually want mining or logging and the initiative is taken on that side, things will have to be renegotiated.

Meanwhile, Latin America remains among the most dangerous places to be an environmental activist.