U.S. Halts Access to Key Weather Data, Raising Global Climate Concerns

The Pentagon’s decision to block public access to critical satellite weather data is drawing concern among scientists and forecasters, particularly in the Global South, where forecasting tools are limited and extreme weather events are intensifying.

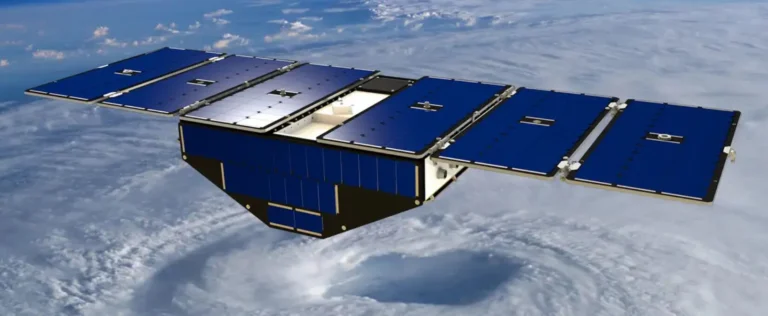

Experts warn the U.S. satellite data cutoff will widen the climate information gap between North and South. Photo: DW

July 10, 2025 Hour: 3:19 am

Starting in late July 2025, the U.S. military will stop sharing key satellite-based weather data with civilian scientists. Announced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the move—justified on security grounds—has raised concerns among climate experts about its global implications, especially for countries with fewer technological resources.

RELATED:

Houthis Sink Israeli-Bound Ship in Red Sea: Yemen’s Naval Resistance Against Imperialist Aggression

The Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP), operated by the U.S. Air Force since the 1960s, has long provided essential atmospheric, oceanic, and geophysical data. The system is currently run from a base in Nebraska, and data collected has been routinely used by both military operations and civilian forecasting models.

Among the tools affected are the Operational Linescan System (OLS) and the Special Sensor Microwave Imager Sounder (SSM/IS), which gather critical information on cloud distribution, atmospheric temperatures, humidity, and radiation. These instruments have played a central role in enhancing the accuracy of global forecasts.

“The atmosphere is a chaotic system where even small variations in temperature, pressure, and wind can trigger significant effects far from their origin,” explained meteorologist Peter Knippertz of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in an interview with DW. He warned that the loss of U.S. satellite data would lead to “a statistically measurable drop in forecast accuracy.”

Until now, this satellite data was processed by the U.S. Navy’s Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center and made available to research institutions and the public. That open access will end this month.

In response, meteorologists and climate researchers are now seeking alternative data sources and recalibrating their models. For example, the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) plans to use Japanese satellites to continue tracking Arctic sea ice—data that’s critical for international shipping and global climate monitoring.

While NOAA insists that the remaining U.S. satellites will compensate for any data gaps—particularly for hurricane forecasts—experts warn this may not hold true for regions in the Global South. In areas where data must still be gathered manually, the loss of access to U.S. satellite information could significantly weaken forecasting capabilities.

“This is especially concerning for countries with fewer resources to invest in alternative monitoring infrastructure,” said Knippertz. “The absence of this data will hit hardest where it’s needed most.”

Adding to the concern, U.S. media have reported that the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawai‘i is also being shut down. In operation since 1958, the station has been one of the most important sources for monitoring carbon dioxide levels and documenting the human impact on climate. While this closure appears to be driven by political rather than security motives, it further reduces global access to long-standing climate data.

As extreme weather events become more frequent and severe, experts argue that access to meteorological data must be expanded, not restricted. For many countries in the Global South, the loss of these U.S. satellite resources represents more than a technical gap—it is a setback for climate justice and global scientific cooperation.

Author: MK

Source: DW