Colombian Court Declares Former President Álvaro Uribe Guilty

File photo taken on November 27, 2023, of former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe Vélez speaking during a press conference in Bogotá, Colombia. Photo: EFE/ Carlos Ortega

July 28, 2025 Hour: 5:32 pm

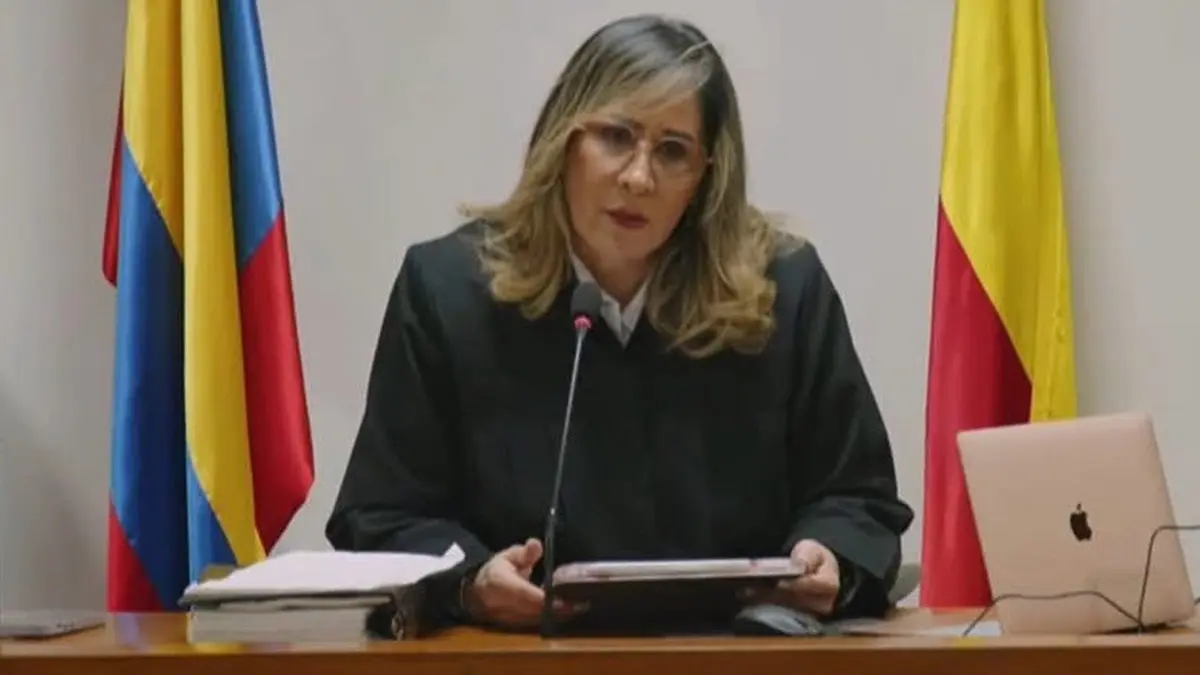

In a landmark ruling, Judge Sandra Liliana Heredia of Bogotá’s 44th Criminal Court found former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez guilty of procedural fraud and witness tampering.

RELATED:

Colombian Judge Heredia To Issue Sentence Against Ex-President Alvaro Uribe

Uribe, who served as president of Colombia from 2002 to 2010, was accused of orchestrating a scheme through his former lawyer, Diego Cadena, to manipulate judicial proceedings by pressuring and bribing witnesses. Specifically, the case involved attempts to persuade jailed ex-paramilitaries to retract statements linking Uribe to paramilitary activities—offering them legal favors in exchange.

The verdict follows more than a decade of legal battles. The process began in 2012 when Senator Iván Cepeda presented allegations implicating Uribe in the creation and support of paramilitary groups. While initial investigations focused on Cepeda, they eventually shifted to Uribe, culminating in formal charges in 2019. After a brief period of house arrest in 2020, Uribe resigned his Senate seat and the case moved from the Supreme Court to ordinary criminal jurisdiction.

The trial, one of the most consequential in Colombia’s democratic history, featured nearly 90 witnesses and extended over 67 hearing days. Prosecutor Marlene Orjuela requested convictions on all charges, while Uribe’s defense team insisted on his innocence and claimed political persecution.

This verdict marks the first time a Colombian ex-president has been convicted in a regular criminal court. However, the ruling is in first instance, which means both the prosecution and defense have five business days to file appeals. If upheld, Uribe could face 6 to 12 years in prison, although alternative sentences such as house arrest may be considered if the sentence is less than eight years.

Legal analysts note that the case may still take years to reach final resolution. Appeals could be heard by Bogotá’s High Court, and potentially reach the Supreme Court’s Criminal Chamber, which may take up to five years for a definitive ruling.

Another point of legal debate is whether the statute of limitations could nullify parts of the case by October 2025, depending on procedural delays and appeal timelines.

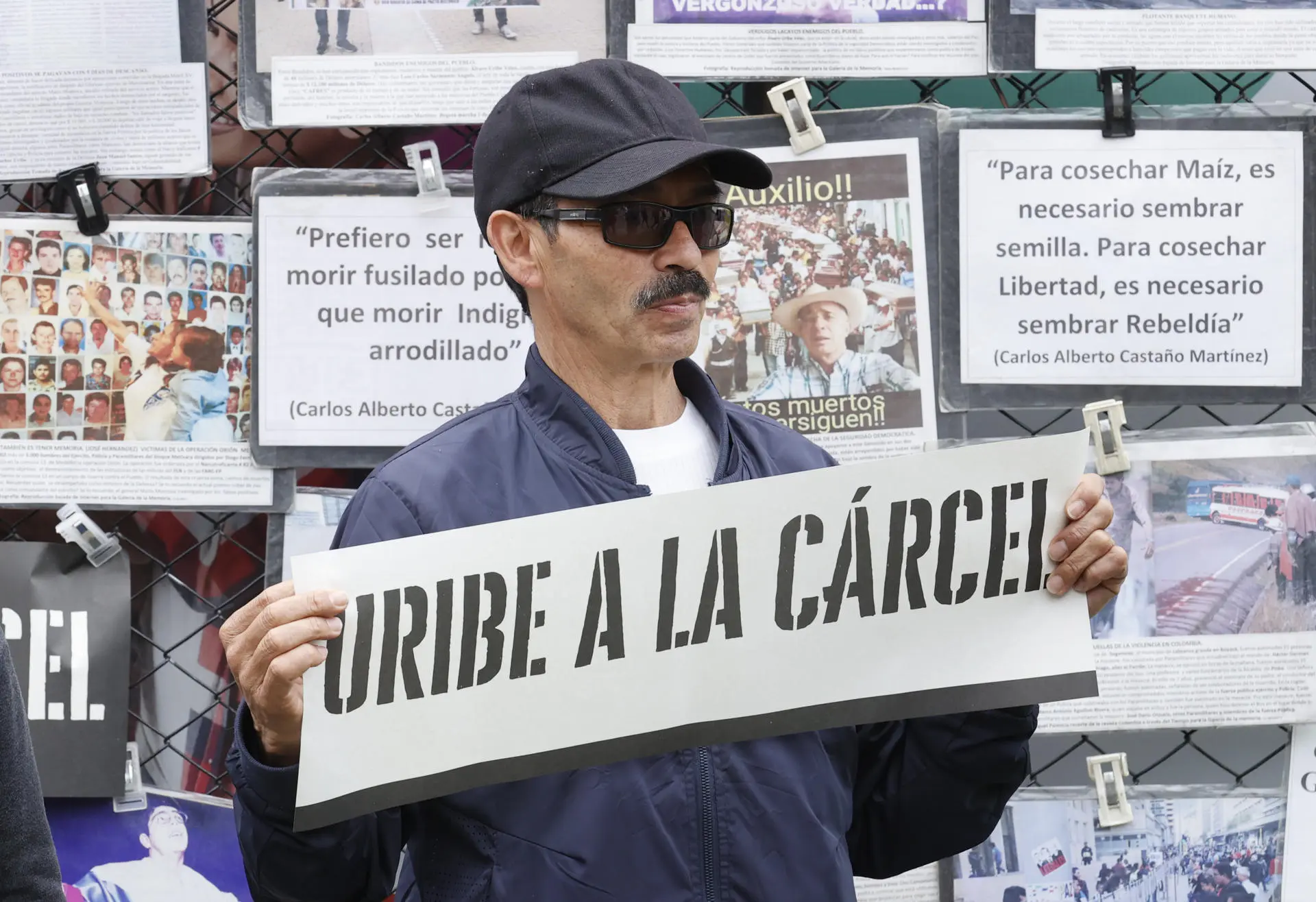

Beyond legal consequences, the ruling could reshape Colombia’s political landscape. Uribe remains a powerful figure through his Democratic Center party, and his conviction may affect the 2026 electoral climate. His critics hail the ruling as a triumph for judicial independence, while his allies denounce it as a politically motivated attack.

President Gustavo Petro responded to the verdict by urging respect for judicial decisions and reinforcing his administration’s commitment to institutional integrity.

Senator Iván Cepeda, a central figure in initiating the investigation, declared: “Justice arrives, even if late.”

The case has become a touchstone for broader debates about accountability, impunity, and the rule of law in Colombia—a country long marked by political violence and deep institutional mistrust.

As appeals move forward, the nation watches closely, aware that this verdict may signal a turning point in its pursuit of justice, regardless of rank or political legacy.