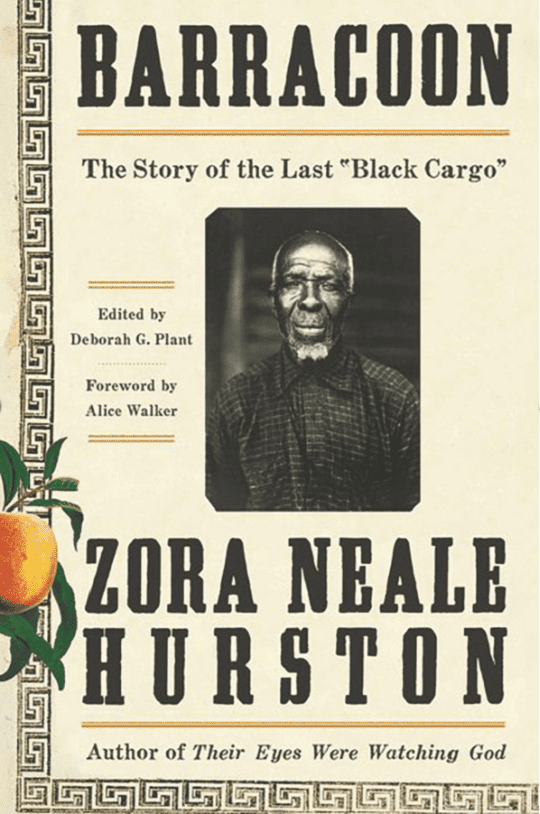

In a milieu rife with hate crimes, and police brutality against Black people in the United States, Zora Neale Hurston's recently released book, "Barracoon; or the Last Black Cargo" makes an essential read as it contextualizes the white supremacy and humanizes the life of a slave which for the most part is a rarity in the canon of Black literature in the United States.

RELATED:

Of ‘Broken Backs’ and Mighty Pens: How Radical Black Women’s Writings Shaped Social Movements

Hurston who died in 1960 has left behind an extensive literary legacy of prominent writings, ranging from anthropological works to fiction. She is most known for her seminal work, "Their Eyes Were Watching Us" in 1937 novel, which came at the tail-end of the Harlem Renaissance, in which she describes the precarious plight of “strong Black women” as the “mules of the world" through a strong Black woman's character.

The 117-page manuscript published by Harper Collins chronicles the life history of Cudjoe Lewis, who was born in West Africa, abducted and sold as a slave in Alabama six years before the Civil War ended. He was 86 when Zora Neale Hurston interviewed him.

Lewis along with 116 other Africans were captured from Dahomey, in what is today Benin in West Africa, in May 1859 and sold to Captain Foster. Foster who was traveling at the request of the Mehear brothers, three U.S. slave traders originally from Maine but who later relocated to Alabama where they operated a shipyard.

After three months, the newly enslaved were sold at Mobile Bay in Alabama, where the ship was docked but since the transatlantic slave trade was abolished some fifty years earlier, once the Mehears landed on U.S. soil the ship was "scuttled and fired," the remains of which were later found at the bottom of Mobile Bay.

The literature on the African slave trade, Hurston wrote, had endless "words from the seller, but not one word from the sold." And through the book, Hurston seems to have managed to not be Lewis' voice but instead use his voice.

Through this essential piece of literature, critics have marked one of Hurston's most eminent contribution as giving the ownership of Black persons who were transported through the Atlantic against their own will back to them.

The text which is just a little over a hundred typed pages is narrated mostly in Lewis' voice, in which he recounts anecdotes about his childhood in Africa, the Middle Passage, the five years he spent enslaved, and his post-emancipation life.

The work, which Hurston once described as a testament to Lewis’s “remarkable memory,” details his cultural traditions, games, folktales, religious practices, and day-to-day activities. According to HarperCollins, the book “masterfully illustrates the tragedy of slavery and of one life forever defined by it. Offering insight into the pernicious legacy that continues to haunt us all, black and white, this poignant and powerful work is an invaluable contribution to our shared history and culture."

The work, which took a little less than 90 years to make it to the press, also has a long history of rejections at the hands of editors it was shared with during the 1930s when it should've first been published.

"In 1930, Hurston floated the idea past Mason: “In the last chapters of the book I shall let Kossula tell his little parables. When I see you next tell me what you think of the idea.” Evidently, Mason didn’t think much of the idea. Not only did Hurston end up reducing the parables to a list, but the collection was never published during Hurston’s lifetime," Autumn Womack, a New Jersey-based scholar and a professor of African American Studies and English at Princeton University, wrote in Paris Review about Hurston's book.

"Slavery and its 'pernicious legacy' does, indeed, continue to 'haunt' us. We are, as many scholars have put it, living in the afterlife of slavery," Womack wrote.

Saidiya Hartman, a professor who specializes in African American literature and history at the Columbia University, wrote, "If slavery exists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery–skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment."

Hurston who frequently exchanged letters with Langston Hughes, while she was researching for the book in the South, concluded in a 1929 letter, “OH! almost forgot. Found another one of the original Africans, older than Cudjoe about 200 miles upstate on the Tombighee river. She is most delightful, but no one will ever know about her but us. She is a better talker than Cudjoe."