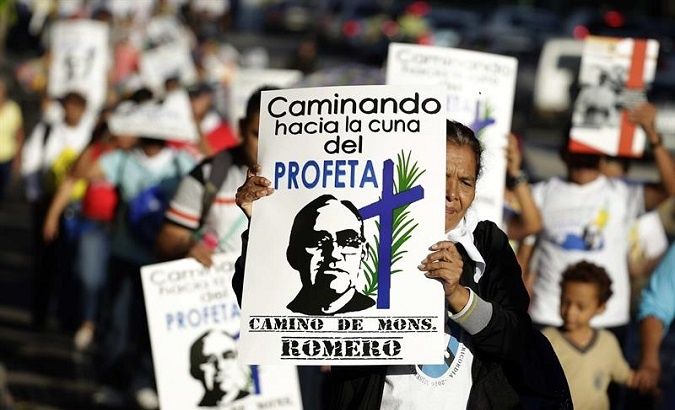

One hundred years after he was born, the life of Oscar Romero, "the bishop of the poor" as he became known, is being celebrated around the world.

RELATED:

El Salvador Judge Reopens Case of Slain Archbishop Romero

Cardinal Ricardo Ezzati, special envoy of Pope Francis to El Salvador, is celebrating a special mass in his honor on August 15.

Thousands of others are marking the occasion in dozens of other countries.

The Salvadoran Archbishop's assassination in 1980 sent global shockwaves, but his killers have never been brought to justice.

The case was recently reopened by Judge Rigoberto Chicas, on May 18, in the wake of the Salvadoran Supreme Court's revoking of an amnesty law.

Romero was beatified in 2015, the last stage before canonization.

Millions of Catholics continue to revere his teachings, his beliefs and above all his example.

"At the international level, Monsignor Romero is the most respected, best known and most beloved person in El Salvador," said Carlos Vaquerano, executive director of the Salvadoran Leadership Education Fund.

Life

Born in 1917 to Santos Romero and Guadalupe de Jesus Galdamez in Ciudad Barrios in the San Miguel department of El Salvador, Oscar Romero was baptized into the Catholic Church by Father Cecilio Morales.

Romero began to train as a carpenter, where he showed proficiency as an apprentice. But he opted to enter the Church instead.

Romero entered the minor seminary in San Miguel at the age of 13.

After graduation, he enrolled in the national seminary in San Salvador. He completed his studies at the Gregorian University in Rome, where he received a Licentiate in Theology cum laude in 1941, but had to wait a year to be ordained because he was younger than the required age. He was ordained in Rome on April 4, 1942.

He embraced a simple lifestyle; he was a popular preacher who responded with real compassion to the plight of the poor.

He gave dedicated pastoral service to the diocese of San Miguel for 25 years.

There followed seven years of what he called "pastoral famine," while he served as an ecclesiastical bureaucrat in the capital city, San Salvador.

Ordained Auxiliary Bishop in 1970, he gained a reputation as a stubborn and reactionary prelate.

Seemingly unsympathetic to the new social justice thrust of the Latin American Church, he was suspicious of the clergy and the Base Christian Communities of the archdiocese working alongside the exploited rural poor, promoting social organizations and land reform.

RELATED:

Leader Who Evaded Justice for Human Rights Abuses Buried with Honors in El Salvador

But within three weeks of being appointed Archbishop of San Salvador in February 1977, Romero's stance changed. His friend and priest, Rutilio Grande, was murdered along with two parishioners. Grande had been working with the campesinos to promote cooperatives. Romero drove to the community of Paisnal to view the bodies and meet the peasants who were facing mounting repression. From that day on, Archbishop Romero became a staunch critic of the military government, blaming it for the killing, kidnapping and arresting of priests, campesinos and activists who were organising peasants and supporting workers’ rights.

Violence and murder were claiming the lives of 3,000 people each month. In the words of one witness: "The streets were flooded with blood." The organisations that would soon form the Farabundo Marti Liberation Front, FMLN, were organizing resistance.

A brief spell back in the countryside as Bishop of Santiago de Maria further opened Romero’s eyes as he reconnected to the semi-feudal misery and hardship of the campesinos and witnessed the murderous repression being suffered at the hands of the security forces.

Death

His sermons, often broadcast on radio, riled the rightwing extremists in the army, the government and El Salvador's business elite. But he ignored multiple death threats, remaining defiant up to his murder while giving mass in the chapel of a San Salvador hospital.

Romero demanded justice and recompense for the atrocities committed by the army and police and he set up legal aid projects and pastoral programmes to support the victims of the violence.

He was vilified in the press, attacked and denounced to Rome by Catholics of the wealthy classes, harassed by the security forces and publically opposed by several episcopal colleagues.

Two months before his death, Romero wrote to the U.S. President Jimmy Carter to ask him to stop sending military aid to the government of El Salvador. "It is being used to repress my people," he wrote. He received no answer. The United States continued to send US$1.5 million in aid every day for 12 years.

RELATED:

El Salvador Govt Asks for Forgiveness for 1981 Massacre

Archbishop Romero realized he was going to be killed. And he came to accept it.

On March 23, 1980, he broadcast the homily which many believe sealed his death warrant. With his voice rising, he addressed the ordinary soldiers, most of whom came from campesino families: “In the name of this suffering people, whose cries to heaven become more deafening each day, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: stop the repression.”

At 6.26 p.m. on the following day, March 24, 1980, with a single gunman’s bullet, he fell at the foot of a huge crucifix as he was celebrating Mass in the chapel of the Divine Providence cancer hospital in San Salvador where he lived.

A week later, on March 30, more than 250,000 mourners attended his funeral at San Salvador's cathedral. Some called it the biggest demonstration in the country's history. During the ceremony, smoke bombs exploded outside and snipers fired on the crowds from surrounding buildings, including the presidential palace. Between 30 and 50 people were killed.

In the months that followed, El Salvador's conflict turned into an all-out armed conflict between government forces, backed financially and militarily by Washington, and the guerrillas of the FMLN. The conflict claimed about 75,000 lives.

Beliefs

The Archbishop boldly preached a message of social justice.

In his homilies and pastoral letters and on his radio broadcasts, Romero condemned the country’s oligarchy and violence.

At the time, El Salvador was ruled by “14 families,” a small class of Salvadoran big landowners and businesspeople who owned virtually all of the land.

RELATED:

The End of Impunity in El Salvador?

Campesinos were rising up against the feudal regime, demanding ownership of their land; the military responded with brutal repression.

Archbishop Romero excommunicated those who killed the priests who tried to protect the rural poor.

Although, Romero did not openly embrace the Libertion Theology movement, his defense of the poor and criticisms of the Salvadoran government dovetailed with the aims of that movement which had taken root in many parts of Latin America.

While today the Salvadoran hierarchy welcomes his designation as a martyr, Romero received little support at the time from his fellow bishops who were more worried about Marxist revolutionaries than military abuses.

Nor did he get support from the Vatican. Pope John Paul II knew little about Latin America and took advice from conservatives like Colombian Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo and Cardinal Angelo Sodano, who as Vatican nuncio to Chile had been friendly with President Augusto Pinochet.

Legacy

Romero’s path to sainthood stalled under popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI, but Pope Francis restarted the process in 2013 and declared him a martyr in 2015.

But almost four decades after his murder, the killers remain free.

RELATED:

'I Am Proud to Be a Leftist President': El Salvador's Sanchez Ceren

Author Matt Eisenbrandt, who's book "Assassination of a Saint" details Romero's murder said, “There are clear (evidential) threads on who gave the original order and who paid for the murder that any concerted investigation in El Salvador would absolutely be able to gather enough evidence to prosecute those involved.”

Eisenbrandt was part of a team of crusading human rights lawyers from the San Francisco-based Centre for Justice and Accountability who used an obscure U.S. law, the Alien Torts Act, to successfully bring a civil case against one of the conspirators in Fresno, California, in 2004.

Former Air Force Captain Alvaro Saravia went into hiding before the verdict, but later admitted to participating in the plot, and remains the only person held responsible for Romero’s murder in a court of law.

A report by the United Nations Truth Commission, which investigated human rights violations during the 12 year conflict, determined that former Army major and founder of the right-wing Nationalist Republican Party, Roberto D 'Aubuisson, gave the order to assassinate Romero.

Last year, the Salvadoran Supreme Court struck down an amnesty law, enabling victims to seek reparations and the government to prosecute atrocities committed during the war.

Reopening the Romero case could also pave the way for the highly polarized country to confront its past, joining the ranks of countries like Chile, Guatemala and Peru that abolished amnesty laws and prosecuted high-ranking war criminals.

"The Romero case is unlikely to have a live defendant, but it has extraordinary symbolic power," Stanford University Professor Terry Lynn Karl said.