It was earlier this summer on July 1st, when I protested in New York in front of the Dominican Consulate. Dubbed “the National Day of Action,” Dominicans and many others across the country protested against the government of the Dominican Republic following a court ruling that denationalized thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent. We gathered to denounce the government’s policies and express solidarity with the denationalized.

The demonstration received some attention due to the Dominican Consulate’s prime location, right in Times Square. As I filmed the protest, I saw a Dominican man who was watching on the sidelines and I asked if I could record him and his son for a video on my blog.

Pulling me to the side and away from the crowd, he whispered in Spanish, “You want me to tell you the truth?” he asked, as his eyes enlarged and his hands beckoned me. “I don’t agree with none of that, I don’t want Haitians around!”

I was taken aback by the anger I saw in his eyes, and I immediately left to continue filming the group.

Three days later, I posted the resulting video on my Facebook page, Radical Latina. I use the Radical Latina blog to write about political issues and personal experiences from my own perspective as a Dominican-American Afro-Latina. The video was meant to serve as a report as well as an opportunity for Dominican-Americans in New York to send a message to Dominicans in the Dominican Republic. Within the first few days, it got thousands of views and, at first, mostly positive reactions.

Intimidating Those Who Dissent

However, two weeks after the video’s creation, dozens of users flooded the comment section with messages against the protest ranging from violently patriotic statements like, “Patria (Homeland) or Death” to racist generalizations calling Haitians “violent.” Initially, I tried ignoring them. But then the private messaging began along with comments on the main page.

As if this wasn’t enough, some users began critiquing an older video of a similar protest which had over 200,000 views, accusing me of being attention-seeking by posting the political actions of dissent.

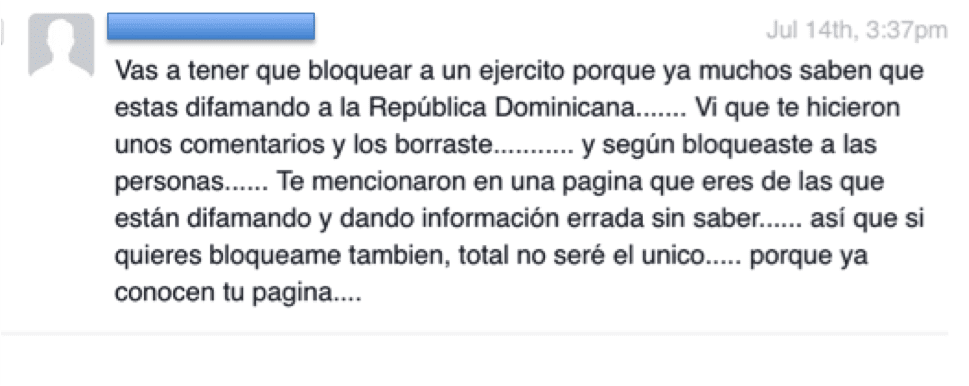

I immediately started deleting these comments and blocking users. But that’s when someone posted this:

“You’re going to have to block an army because many already know that you’re defaming the Dominican Republic.”

I was frightened.

In just one day I blocked about 100 users, who left messages like this. Deleting all the comments that had been previously made on the video to stop the discussion which escalated into racist remarks and claims against those who I had interviewed in the video.

In private messages, I was taunted and in other older posts, commenters logged on to call me a “Bruja” (witch) and a “traitor.”

Even seemingly friendly users said “Hey Radical Latina, if you are Dominican, why are you speaking bad about your country?”

Under a photo I posted of myself with a t-shirt of the Haitian flag to show solidarity (see above), the comments weren’t just vile, many times they were threatening.

“I wish I could meet one of these people in person,” one user wrote. “I’ll teach them how to respect our flag.”

Intimidating Those Who Report

But I’m not the only one. When Huffington Post reporter Roque Planas, who’s covered migration issues, was in the Dominican Republic reporting on the week before the deportation deadline for obtaining citizenship, he faced online harassment as well.

“My policy has been to consistently engage and respond to anyone who I don’t feel is being particularly obnoxious, or who is coming from a point of view where they’re trying to understand,” he says.

“But I got a lot of (online harassment from social networking users), with some I’d maybe go 30-40 tweets back and forth, before it eventually stopped. I blocked some of them.”

Planas found that there were often dozens of people at times who would try to engage with him with a set of ultra-nationalist talking points.

“I found that there was sort of a little army of Dominican nationalists that were popping up from time to time … and that were basically dedicated to going around and sort of approaching journalists who were covering the issue.”

Planas noticed a level of organization to some tweets and comments.

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it was a manufactured campaign, because the people that I engaged with, many of them were clearly interested in talking about the issue and had some knowledge of it,” he said. “But there was some level of organization because there were just hundreds of accounts popping up with no followers with the same talking points.”

However, a manufactured or orchestrated campaign actually seems like the perfect way to describe the online trolling. After searching, I found the page that the commenter who warned me about an “army” was referring to. Apparently, my video had been posted on the Facebook page “Por La Soberanía Dominicana Ahora” (For Dominican Sovereignty Now) which has over 9,000 followers, as well as the page Dominicano Viral with a smaller following.

The comments under the “Por La Soberanía Dominican Ahora” page included users who admitted to having commented on the Radical Latina page, yet their profile names didn’t match. One user even admitted that he had been blocked. This made it likely some of these folks created fake accounts just to leave comments on Radical Latina (and perhaps other pages).

Artists as “Traitors”

A person who is familiar with online trolling campaigns led by Dominican ultra-nationalists has been Dominican-American and Bronx artist Yelaine Rodriguez. Rodriguez curated an art exhibit in February, titled “La Lucha: Quisqueya & Haiti, One Island” which translates to “The Struggle: Dominican Republic and Haiti, One Island.”

For Rodriguez her art was designed “to educate the viewers and ourselves, about the history of the land in which modern day Dominican Republic and Haiti reside. We want to spark a conversation between the two nations that is very much needed,” she said.

But the exhibit garnered a lot of online animosity. Rodriguez recounted deleting three to six comments a day, especially after it gained a lot of attention from an article on DNAinfo.com.

Dominican-American and Bronx artist Yelaine Rodriguez stands next to a display in her La Lucha exhibit. | Photo: Roberto Calansanz

“When I started to talk to people about La Lucha, that's when I began to see the sea of people separating and picking sides … People had a lot of issues with the title ‘La Lucha: Quisqueya and Haiti: One Island’. They were saying that I wanted to unite the island, that I was pro-fusionist, that I was ‘Vende Patria,’ (Selling the Homeland),” says Rodriguez.

She emphasized that she was open to dialogue, but that “La Lucha is not about blaming one another, it is a collective of artists that happen to be linked to the same island.”

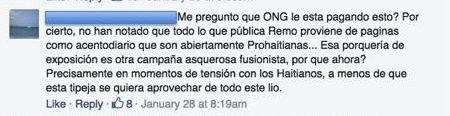

The same article was then translated to Spanish and shared on Remolacha.net, a popular page with over 190,000 likes. The comments by Dominicans who often claim to be “protecting” Dominican identity swarmed in:

“Remolacha, in the name of our community, that is truly Dominican, don’t promote this garbage, I’m asking for our country!”

“These artists know the topic will bring them attention. Whichever artist that is truly Dominican would never get involved with an exhibit that wants to fuse the island together. So I doubt that they’re real artists, and I’m sure that they aren’t Dominican!”

“This artist was born here and she doesn’t know shit about what happens over there. She’s only Dominican when it’s convenient for her and only speaks Spanish when it’s convenient. This page is filled with pests like that.”

“I wonder which NGO is paying for this. By the way haven’t you noticed that everything published in Remolacha is usually from pages like Acento Diario which are openly pro-Haitian. This crap of an exhibit is another disgusting campaign to unite the island, why now? Precisely during times of tensions with Haiti, unless this woman wants to take advantage of this mess.”

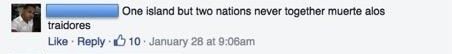

“One island but two nations never together, death to the traitors.”

The fact that one of the commenters says “Death to the traitors,” explains the stress that could follow these online attempts at silencing dissent.

Rodriguez believes that this is a form of online bullying and intimidation, which has driven many young people to suicide.

“It is surely a tool to intimidate people. We can see it as online bullying – how many times have we read articles about young teens committing suicide because of online bullying? The difference with us, people that are organizing these events, is that we are adults and can manage it better. Eighty-five percent of the time I was able to ignore it.”

A group called Movimiento Patriotico Independiente (the Independent Patriotic Movement) released a statement against the exhibit.

Claims made by this organization include that Rodriguez is actually Haitian, and that the event is backed by the Clintons, with the purpose of uniting the island. This group was actually present at the exhibit where they handed out a printed version of the above statement.

Although the claims made by this group may seem exaggerated, these rumors and conspiracy theories are actually shared by many.

Challenging Ultra-Nationalist Narratives

“People will usually say the same things: ‘What about Haiti?’, ‘What about Haiti not giving the papers that people need to apply for citizenship,’” Planas said.

“And some people say that (reporting on the human rights situation) is some sort of conspiracy to unify the island under one government, which is being carried out by some combination of the Clinton Foundation, the U.S. government and France which isn’t true.”

Some ultra-nationalists claim that activists and reporters are paid to write reports against the actions of the Dominican government. Others attempt to discredit the dissenter by emphasizing their identity, that they are Dominican-American, American, or even just a woman.

The Rights4ALLinDR Twitter Campaign shares an image taken at a Dominican ultra-nationalist protest.

For these nationalists, one can discredit an argument by claiming that Dominicans speaking up against the republic’s policies are in fact Haitians, or they claim that because the Dominican Republic supported Haiti during the 2010 earthquake, Dominicans shouldn’t owe the Haitian people a thing.

The worst arguments tend to be claims that these injustices are completely justified because Haitians are lesser humans. Users who believe this often share unsourced photos of black men and women either engaging in some sort of spiritual practice deemed “taboo” or committing violence against one another as a way to try and take away the humanity of those who are of Haitian descent.

What is missing in most of the commenters who come in waves (as opposed to isolated critics) is a nuanced view that doesn’t discredit a journalist’s article or an activist’s project based on their own projections.

“You must be Haitian” does not discredit an argument because Haitians must be able to speak up about this problem (and be heard). Previous humanitarian action too shouldn’t be used as a way to purposefully attack a population but rather should be understood as two different situations and contexts.

Those who use this logic actually discredit themselves by sharing opinions based on racist and nationalistic ideologies which can easily lead to the present situation or, worse, to incidents of cruel violence on the part of vigilantes in Dominican communities where Haitians reside.

Many of narratives told by the ultra-nationalists are actually in line with messages shared by the Dominican government.

Below is in image shared by one particular troll of a campaign by the Dominican government that promotes Haitians who did obtain documentation. The government also publishes articles on their official website with messages justifying the recent law.

Images promoted by the DR government’s publicity campaign used to discredit undocumented Haitian immigrants. The picture shows an older Haitian man holding legal documents with the words “The country has made me a citizen.”

One particular memorandum claims to share “The True Story” of Haitians without documentation. Among some of the talking points are that the Haitian government must cooperate, that some “forces” are benefitting from the current situation yet are lying about it, and that the Dominican people must unite to support the regularization of Dominicans of Haitian descent.

The government’s memorandum describes Haitian immigrants as people who “cruzan como Pedro por su casa,” an expression used to describe people who go to a new place and act as if “they owned the place.” This particular form of describing those who have been denationalized by the current ruling dismisses the many Haitians who have worked in the Dominican Republic for years and who have had to endure the struggles that migrants face when entering new territory, a new territory that in fact isn’t new for many Haitians who have lived in the country for many years and have come to identity as Haitian-Dominican.

More Than Just Online Intimidation

Some Dominican journalists have actually received death threats for covering this issue.

This silencing of dissent and ultra-nationalist anti-Haitian sentiments are easily remnants of Rafael Leonidas Trujillo’s dictatorship.

During the 1930s, Trujillo spread and promoted the sentiment of anti-Haitianism in the country, eventually ordering the killing of many in what became known as the Parsley Massacre.

His presidency was followed by the democratic election of Juan Bosch, until a U.S.-backed coup d'etat and subsequent occupation led to the instatement of Joaquin Balaguer as president.

Balaguer’s government was behind the death of notable journalist Orlando Martinez, someone who has become a symbol of freedom of expression in the Dominican Republic.

Despite this history, many would prefer to blame Haitians themselves for the anti-Haitianism in the Dominican Republic because of the so-called “Haitian Occupation” of 1822 under Jean Pierre Boyer, and even the story of the Deguello de Moca earlier in the 1800s – both historical periods are often misrepresented.

Activist Matías Bosch recently wrote in an article where he reminded Dominicans that the fight against Boyer’s dictatorship in the Dominican Republic in 1843-1844 was fought side by side with Haitian supporters. The Deguello de Moca, that is accounts of a massacre of over 500 people by Haitians in what is today the Dominican town of Moca have also been exaggerated to make it seem like more folks were killed. Therefore, the current sentiments and talking points used by ultra-nationalists have more notable roots in Trujillo, and his legacy remains.

A meme used by troll on the comments of the "Por La Soberanía Dominicana Ahora" Facebook page, with an image of Dictator Rafael L. Trujillo, who ordered the massacre of Haitian workers. The text says, “Oh, If only I was a alive...”.

Nonetheless, international accounts of the situation often lack nuance in their explanations about where these sentiments come from, and oversimplify the situation, blaming the Dominican people rather than government policies or issues of inequality.

“To their credit, and a lot of debate around this issue has been driven by human rights organizations giving information to people outside the country, outside of the Dominican Republic who really don’t understand the issue that well,” says Reporter Roque Planas.

Planas adds that the hostile nationalism seems to come from a place of vulnerability.

“You’re talking about a people that are stuck in a situation where they feel powerlessness.”

Dominicans are also victims, including the online trolls, who live in a country that has been plagued with a history of oppression, including the U.S. occupations and the Trujillo Era as well as present day-to-day inequality and government corruption.

Still, many questions remain about these internet ultra-nationalists: are these in fact manufactured campaigns to silence critics of the rulings, if so who is behind them? Or are these users simply Dominicans who feel entitled to defend what they have been told is the truth about their identity and current socioeconomic situation?

One thing is certain, journalists, activists, and those who are working to start a safe dialogue about the Dominican Republic and Haiti won’t be silenced by the online trolls.

“(They) didn’t intimidate me,” declares Planas, “I think in some ways it made me a better reporter.”

Rodriguez, who is currently planning the second installment of the exhibit, will not be silenced by the comments either.

“I didn't feel threatened, my mother raised me to believe that things are always possible, that I should act with my heart.”

Amanda Alcantara is a writer, a journalist, and an activist. She is the Co-Founder and Editor-in-Chief of La Galería Magazine, a magazine for Dominicans in the Diaspora, and author of the blog Radical Latina. Amanda writes about the intersections of gender and race from a political and personal perspective. She received her Bachelor’s degree in Journalism & Media Studies and Political Science from Rutgers University, with a minor in French Literary Studies. She is currently pursuing an MA in Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University. You can follow her on Twitter at @radicallatina.